Off the coast of Japan, a wave forms and then intensifies as it propagates four thousand miles eastward across the Pacific Ocean. High above, westerly winds gather moisture-laden clouds as they blow over the warm waters. When both of these elements meet land for the first time, it is a force to be reckoned with.

Welcome to the west coast of Vancouver Island, where warm moist air masses, forced upward by the island’s mountain ranges, dump their weight of water on the coastline below as ferocious waves pound the rugged shore.

Captain Harry Scougall and thirty-five others aboard the Pass of Melfort didn’t survive the double blow they were dealt by the elements off Amphitrite Point on Christmas Day, 1905.

The Pass of Melfort and its Captain were not originally scheduled to make their trip to the Northwest that ended that dreadful winter day. The story going around at the time was that the Pass of Branden, a sister ship to the Melfort, had been assigned to make the trip, but when a more favorable charter came in, the owners dispatched the newer Branden to the Antipodes and in its place sent the four-masted, steel-hulled Melfort to Seattle for a load of timber.

That autumn, when the voyage was being arranged, the owners approached Captain Scougall, a fifty-five-year-old retired veteran, and asked if he wouldn’t mind taking the voyage since the current captain appeared to be useless. Captain Scougall, a kind, friendly chap, agreed “out of consideration for his former employers.”

Thirty-eight days after setting off from Panama, the Pass of Melfort met up with Captain Olsen and the British bark Broderick Castle off Southern California. The Captains signaled that they were both headed to the Puget Sound, but when Captain Olsen landed at Port Townsend, he was surprised to learn the Pass of Melfort wasn't there. Olsen speculated that the Pass of Melfort had been caught in the storm he encountered off the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where he had to perform “the toughest bit of sailing he had ever done.”

The Pass of Melfort had missed the Strait and was driven further north by the relentless storm. First Nation people saw a distress rocket over the Uncluth Peninsula on the north shore of Barkley Sound just before dawn on Christmas Day and paddled with the news to the village of Ucluelet.

Both settlers and members of the First Nation scoured the area for signs of a ship, and soon discovered the grim remnants of the Pass of Melfort on a reef, just east of Amphitrite Point, fifty yards from shore. Even as they were combing the shore in hopes of finding survivors, the monstrous seas continued to batter the rocks and “rush into the bay as though in a tide race.” No survivors were found.

Just two weeks before the wreck, the whistling buoy marking the reef had disappeared in heavy seas.

After the Christmas Day tragedy, the shipping industry pressed for a light at Amphitrite Point, and in January 1906, the Department of Marine and Fisheries authorized the construction of a small square wooden tower, painted white and located on the outermost high rock at the point. The tower, which cost $141.54, was equipped with a dioptric lens holding a three-wick, 31-day Wigham lamp. The coxswain of the lifeboat station at Ucluelet was charged with maintaining the light, which the Victoria Times predicted “should prove of incalculable value to a vessel drifting in close to the island shore on such a night as the one in which the Pass of Melfort went to her doom.”

The tower withstood tumultuous tempests for eight years until January 2,1914 when a tidal wave demolished it. The very next night, a replacement lantern was hung from the look-out station situated further back from the bare rock.

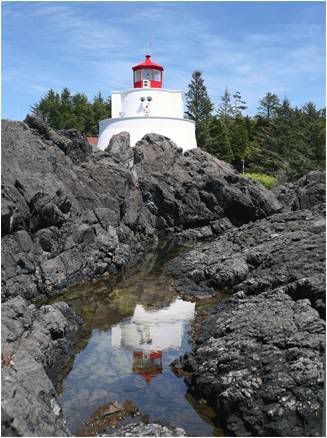

Sea captains requested an “up-to-date lighthouse, a wireless station and fog alarm at or near Amphitrite Point,” and construction of the current one-of-kind squat tower began in January 1915.

Originally, the plan was for the tender Leebro to land supplies at the site, but high tides and heavy surf hampered the effort, so instead small vessels were used to lighter supplies ashore. Marine Agent H. L. Roberston, the foreman, wrote, “the last time they attempted the passage with a load in the workboat, they nearly upset & that has put the fear of the Lord into them . . . the surf was breaking right up against the base of the rock & sweeping clear over the top of the high rock to SE of site.” The remaining supplies were wisely landed at the lifeboat station and hauled overland to the construction site. With the steady winter rains, the road turned into “a mass of mud from one end to the other” and within a week had disappeared under six inches of sucking mud.

Despite the weather, the workers kept on schedule, blasting 125 yards of rock, hauling seventy cubic yards of gravel and 420 sacks of cement, and pouring six cubic feet of concrete every three minutes during their fourteen-hour workdays. The lighthouse went into operation in March 1915. It stands six metres (twenty feet) tall, with a focal plane of fifteen metres (fifty feet) and flashes a white light every twelve seconds.

The Ucluelet lifeboat crew maintained the light and horn until July 1918, when their boat was withdrawn from service. Jim Frazer, who had been maintaining the light, took over as keeper for ten dollars a month, a quarter of what he had previously been earning doing the same job for the Naval Service Board.

The squat tower was not a suitable dwelling, with the diaphone taking up half the living space, and poor ventilation causing steam and foul air to pass through the quarters. Frazer lived a mile from the tower and would hike down every night at sunset, in all kinds of weather, to light the lamp, return at midnight to wind the revolving mechanism, then come back at sunrise to extinguish the light. Frazer’s replacement, Frederick Routcliffe, resigned in 1928, claiming “the present quarters at the station are unfit to live in in very wet weather.” A dwelling was finally constructed in 1929, which included a telephone line connected to the village of Tofino.

In Greek mythology, Amphitrite is the sea-goddess wife of Poseidon. Seven ships of the British Royal Navy have borne the name HMS Amphitrite, and the point on Vancouver Island is named after the sixth of these, a twenty-four-gun, 1064-ton vessel, built in Bombay India and stationed in British Columbia from 1851 to 1857.

The unsheltered waters off Amphitrite Point continue to be pounded by severe winter storms, packing thirty to fifty-foot waves, hurricane force winds, and bone chilling rain - an average of three metres (120 inches) annually. Canada’s one-day record rainfall was set near the point on October 6,1967 – 48.9 centimeters (19.3 inches). Many shipwrecks serve as a testament to the unruly elements, including the Pass of Melfort, now a popular diving spot.

Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário